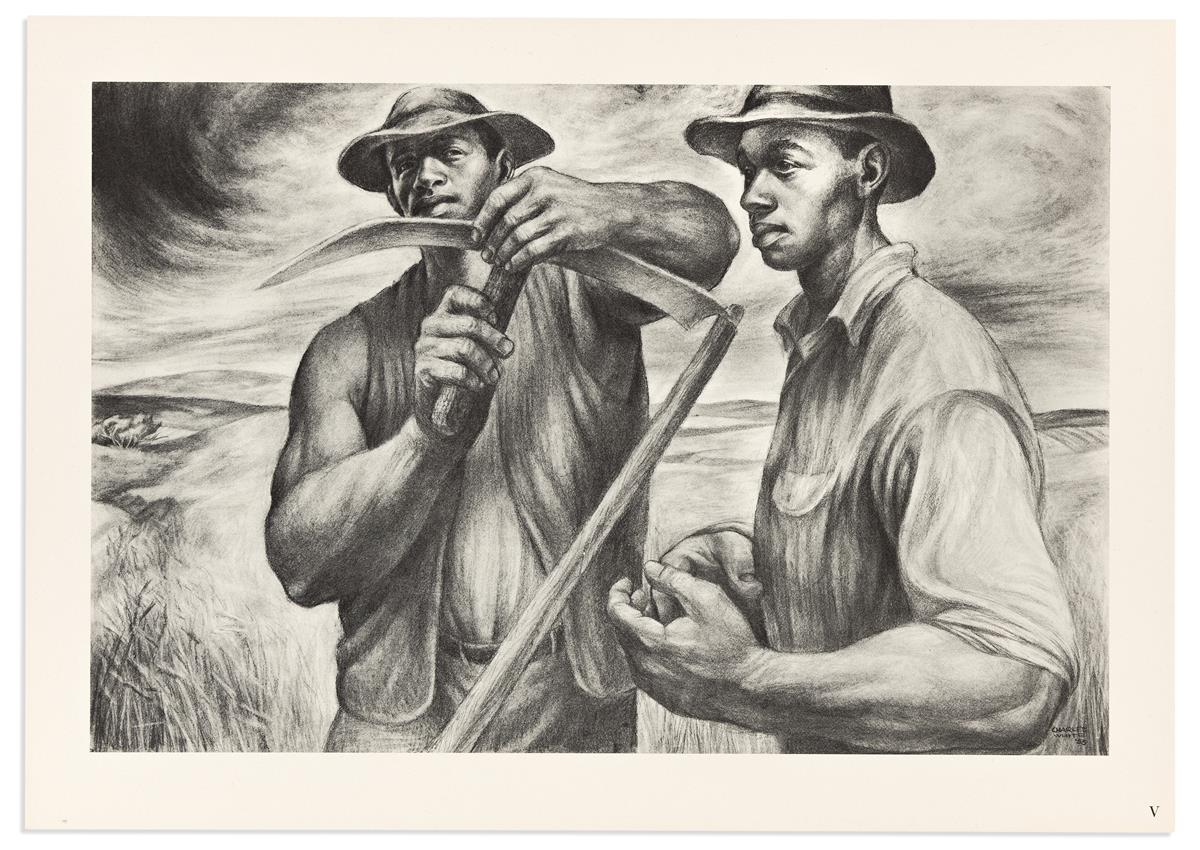

“Harvest Talk” by Charles White

Read this mesmerizing oral history on OLD MASTER, Charles W. White.

The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Charles Wilbert White on

March 9, 1965. The interview was conducted at the Heritage Gallery in Los Angeles, California by Betty Lochrie

Hoag for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

March 9, 1965. The interview was conducted at the Heritage Gallery in Los Angeles, California by Betty Lochrie

Hoag for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Interview

BETTY L. HOAG: This is Betty Lochrie Hoag on March the 9th, 1965, interviewing the artist, Charles Wilbert White

at the Heritage Gallery on North La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles. And this interview is made through the

help of Mr. Horowitz, who owns this gallery and to whom we’re very grateful for making our meeting possible.

Mr. White is one of the leading artists today in graphic arts, in oil painting. He is a teacher and a lecturer and is

outstanding for his contribution to our rich Negro culture in this country. One of the nice things that I think was

said about your paintings was, and your graphics, is that they showed “truth heavy with reality.” I thought that

was very succinct, and I think you should certainly add, by means of lyrical and romantic qualities with the

strength that you have. You particularly concentrated, I believe, in doing paintings of Negro women, especially

from historical sources and ballads, that kind of thing. You’ve had awards so numerous that they’re all listed in

the art indexes, and I’m not going to read them all off because the research students can look all that up. You

have exhibits in leading collections, people all over the United States, and have exhibited in many places and

that list is very long. The Art Institute of Chicago, Howard University, Smith College Museum, Institute of

Contemporary Art in Boston, Atlanta University, Newark Museum, I could go on reading these practically all

afternoon.

Mr. White, before we talk about the Federal Arts Project, which is what we are mainly interested in having

material about for the Archives, I’d like to ask you about your life and your painting. So we’ll start on the history.

First, and before we go into that, I’d like to know if you’d mind if I tell them what the “W” stands for. It’s Wilbert

isn’t it?

BETTY L. HOAG: This is Betty Lochrie Hoag on March the 9th, 1965, interviewing the artist, Charles Wilbert White

at the Heritage Gallery on North La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles. And this interview is made through the

help of Mr. Horowitz, who owns this gallery and to whom we’re very grateful for making our meeting possible.

Mr. White is one of the leading artists today in graphic arts, in oil painting. He is a teacher and a lecturer and is

outstanding for his contribution to our rich Negro culture in this country. One of the nice things that I think was

said about your paintings was, and your graphics, is that they showed “truth heavy with reality.” I thought that

was very succinct, and I think you should certainly add, by means of lyrical and romantic qualities with the

strength that you have. You particularly concentrated, I believe, in doing paintings of Negro women, especially

from historical sources and ballads, that kind of thing. You’ve had awards so numerous that they’re all listed in

the art indexes, and I’m not going to read them all off because the research students can look all that up. You

have exhibits in leading collections, people all over the United States, and have exhibited in many places and

that list is very long. The Art Institute of Chicago, Howard University, Smith College Museum, Institute of

Contemporary Art in Boston, Atlanta University, Newark Museum, I could go on reading these practically all

afternoon.

Mr. White, before we talk about the Federal Arts Project, which is what we are mainly interested in having

material about for the Archives, I’d like to ask you about your life and your painting. So we’ll start on the history.

First, and before we go into that, I’d like to know if you’d mind if I tell them what the “W” stands for. It’s Wilbert

isn’t it?

CHARLES WHITE: Yes.

BETTY L. HOAG: And that’s spelled W-I-L-B-E-R-T and the White is W-H-I-T-E. So, when were you born? And

where?

where?

CHARLES WHITE: I was born in Chicago, Illinois, April 2, 1918. Father was a railroad and construction worker and

worked in steel mills in South Chicago. In his last years he was working at the post office in Chicago. My mother

was a domestic worker all her life. She started when she was about 8 years old, still is a domestic worker, and

now is about 67 or so.

worked in steel mills in South Chicago. In his last years he was working at the post office in Chicago. My mother

was a domestic worker all her life. She started when she was about 8 years old, still is a domestic worker, and

now is about 67 or so.

BETTY L. HOAG: She lives in Chicago?

CHARLES WHITE: Yes, she still lives in Chicago.

BETTY L. HOAG: She must be very proud of you.

CHARLES WHITE: Well, yes, but she wasn’t always enthusiastic about my art. I remember when I was a kid she

was very tolerant and patient with it for a while, and then she saw that I was so dedicated to it, that I had chosen

it for my life’s work, she had second thoughts about whether this was very practical. After all, you know, it’s

much more practical to be a doctor or lawyer with an insured income, and so forth.

was very tolerant and patient with it for a while, and then she saw that I was so dedicated to it, that I had chosen

it for my life’s work, she had second thoughts about whether this was very practical. After all, you know, it’s

much more practical to be a doctor or lawyer with an insured income, and so forth.

BETTY L. HOAG: How early did you show an interest?

CHARLES WHITE: She bought me an oil painting set when I was 7, and from then on I was hooked. Art became

the most important thing in my life. I studied music for about 9 years, violin, which I never had too much

enthusiasm about but she insisted on music. But art became I’d say all-consuming from the time I was 7. Well, in

later years, I studied many things, I became interested in a little dance and I studied modern dance. And I

worked with little theater groups for about 7 years, became interested in all phases of theater. I designed sets

and costumes, even tried to act a little. But back when I was younger, in the grade-school level, or early high

school, art became a thing that was not only all-consuming, but sometimes became a little problem too.

Because I grew up in a very poor section of Chicago, it was a ghetto section, the south side, and these very

formative years, it was at the height of the Depression and—

the most important thing in my life. I studied music for about 9 years, violin, which I never had too much

enthusiasm about but she insisted on music. But art became I’d say all-consuming from the time I was 7. Well, in

later years, I studied many things, I became interested in a little dance and I studied modern dance. And I

worked with little theater groups for about 7 years, became interested in all phases of theater. I designed sets

and costumes, even tried to act a little. But back when I was younger, in the grade-school level, or early high

school, art became a thing that was not only all-consuming, but sometimes became a little problem too.

Because I grew up in a very poor section of Chicago, it was a ghetto section, the south side, and these very

formative years, it was at the height of the Depression and—

BETTY L. HOAG: It was hard growing up anyplace then.

CHARLES WHITE: Yes, besides that, art became a little problem because I grew up where there were a lot of

gangs and art was always considered a little bit effeminate, so I used to go through back alleys to get to my

music lessons and so forth so the kids in the neighborhood wouldn’t see me carrying my little violin along, you

see. And I used to also conceal my interest in art a little bit too because that would have been a problem.

gangs and art was always considered a little bit effeminate, so I used to go through back alleys to get to my

music lessons and so forth so the kids in the neighborhood wouldn’t see me carrying my little violin along, you

see. And I used to also conceal my interest in art a little bit too because that would have been a problem.

BETTY L. HOAG: Probably until they needed somebody to make a sign and then they were glad.

CHARLES WHITE: Yes. You mentioned signs. When I was about 14 I became a professional sign painter. A young

kid who, we were freshmen in high school. And we were both in the art department, and he set up a little sign

painting business. We used to do signs for theaters, beauty shops, barber shops, all the local businesses. We

had quite a little business going there. In fact, we had one theater where we were hired, a movie house, where

we were getting the enormous sum of something like $75 a piece. At 14, and at the height of the Depression.

Then, because we were so young, we couldn’t join the Union, so the Union organized and forced the theater to

fire us. We were so excited about that thing, but sign painting I did up until I was about 18 or 19.

kid who, we were freshmen in high school. And we were both in the art department, and he set up a little sign

painting business. We used to do signs for theaters, beauty shops, barber shops, all the local businesses. We

had quite a little business going there. In fact, we had one theater where we were hired, a movie house, where

we were getting the enormous sum of something like $75 a piece. At 14, and at the height of the Depression.

Then, because we were so young, we couldn’t join the Union, so the Union organized and forced the theater to

fire us. We were so excited about that thing, but sign painting I did up until I was about 18 or 19.

BETTY L. HOAG: One of the articles that I read about you said something about window shade painting. What

was that referring to?

was that referring to?

CHARLES WHITE: Well, my mother, when she bought me this oil paint set, I knew nothing about how to use the

turpentine, how to use the linseed oil that the kit included. So I remember the first time I just poured the linseed

oil into the paint and it naturally became a mess and ran all over everything. But likewise, I didn’t know what

canvas was but I had some vague idea that it had at least a texture I could associate with something that looked

like window shades. So it was the first time I decided to use the set and my mother wasn’t home, so I took a

couple of window shades down and painted on those and my mother gave me an awful spanking when she got

home. What made it happen was that I used to paint for instance on the cardboard and I’d paint on the shirt, you

know, those boards that the shirt, laundry, shirts come in, and one day I was out, we lived not too far from a

park, and one day I happened to be there and there was an art class out there. Some art students from Chicago

and they were all painting landscapes. I watched them carefully all day long. And I found out overhearing some

of the conversation between the students, I found out they were going to be out there for a whole week. So

every day after school I would run to the park and watch to see how they mixed the paints, and how they mixed

their colors, and what they used the linseed oil for, and what they used the turpentine for. And I would go home

each day and try to duplicate what I’d seen, so this, in a sense, was my first art lesson.

turpentine, how to use the linseed oil that the kit included. So I remember the first time I just poured the linseed

oil into the paint and it naturally became a mess and ran all over everything. But likewise, I didn’t know what

canvas was but I had some vague idea that it had at least a texture I could associate with something that looked

like window shades. So it was the first time I decided to use the set and my mother wasn’t home, so I took a

couple of window shades down and painted on those and my mother gave me an awful spanking when she got

home. What made it happen was that I used to paint for instance on the cardboard and I’d paint on the shirt, you

know, those boards that the shirt, laundry, shirts come in, and one day I was out, we lived not too far from a

park, and one day I happened to be there and there was an art class out there. Some art students from Chicago

and they were all painting landscapes. I watched them carefully all day long. And I found out overhearing some

of the conversation between the students, I found out they were going to be out there for a whole week. So

every day after school I would run to the park and watch to see how they mixed the paints, and how they mixed

their colors, and what they used the linseed oil for, and what they used the turpentine for. And I would go home

each day and try to duplicate what I’d seen, so this, in a sense, was my first art lesson.

BETTY L. HOAG: Did they notice and give you any pointers?

CHARLES WHITE: Yeah, they became aware since I was out there every day. But I was very shy and they sensed

that I was, and so a couple of students gave me a few hints about things.

that I was, and so a couple of students gave me a few hints about things.

BETTY L. HOAG: Is that how you found out about the canvas too?

CHARLES WHITE: That’s how I found out about canvas. Not that we could afford it. I still couldn’t use canvas, but

at least I knew what it was.

at least I knew what it was.

BETTY L. HOAG: Well, actually, I would think that window shades wouldn’t be bad.

CHARLES WHITE: No, it wasn’t bad at all.

BETTY L. HOAG: You just couldn’t get anymore?

CHARLES WHITE: No, my mother didn’t seem to appreciate it.

BETTY L. HOAG: Mr. White, did you go to any of the museums there in Chicago and

study painting?

study painting?

CHARLES WHITE: Yes, I knew about the Art Institute of Chicago. The Art Institute of Chicago and the main branch

of the public library were in close proximity. And my mother had developed in me the habit of reading very early

in life. And my mother, when she went shopping, would leave me at the public library and this was the time I was

6 or 7 years old. And so I would go from the Art Institute—sometimes she’d leave me at the Art Institute and I’d

wander through the galleries studying each picture. I remember Winslow Homer became one of my favorites,

and George Inness, early little collections of landscapes. And so between the reading and the Art Institute I

became, I got a pretty good art education long before I could afford to study. But also, at the same time, in

grade school they used to have scholarships that were awarded to the public school students through the Art

Institute of Chicago, with a lecture course. The best art students in every grade school and high school were

given, would be given, a scholarship which lasted for 6 or 7 weeks. So you went on Saturdays and you listened

to a lecture. I remember what the lecturer’s name was, George Burrows, was one of the lecturers and I forget

the other one’s name. The guy would lecture and he’d give you an assignment and it would usually be in an

auditorium with about 5 or 600 kids in it. You would go home, do your assignment and next Saturday bring it in,

turn it in and they would criticize it. A written criticism would be attached to your drawings the next time you

returned. And if it was a good drawing, what they considered good quality, they gave you an honorable mention.

And at the end of the term if you had accumulated something like 10 honorable mentions, you were given a gold

pen which was inscribed. So that was a goal which all students worked toward, they were trying to get this little

gold pen. And so I won these little scholarships consistently until uh, from grade school to high school. But the

other, I guess, the other important thing that happened to me at least in terms of getting some kind of art

education as well as being associated with other young people who were interested in be coming artists, was

that when I was about 14 there was a club, an art club in the Negro neighborhood I lived in and was composed of

all Negro artists. They used to meet on Sundays at various members houses. And we would hold little

exhibitions and occasionally have life drawing classes and things.

of the public library were in close proximity. And my mother had developed in me the habit of reading very early

in life. And my mother, when she went shopping, would leave me at the public library and this was the time I was

6 or 7 years old. And so I would go from the Art Institute—sometimes she’d leave me at the Art Institute and I’d

wander through the galleries studying each picture. I remember Winslow Homer became one of my favorites,

and George Inness, early little collections of landscapes. And so between the reading and the Art Institute I

became, I got a pretty good art education long before I could afford to study. But also, at the same time, in

grade school they used to have scholarships that were awarded to the public school students through the Art

Institute of Chicago, with a lecture course. The best art students in every grade school and high school were

given, would be given, a scholarship which lasted for 6 or 7 weeks. So you went on Saturdays and you listened

to a lecture. I remember what the lecturer’s name was, George Burrows, was one of the lecturers and I forget

the other one’s name. The guy would lecture and he’d give you an assignment and it would usually be in an

auditorium with about 5 or 600 kids in it. You would go home, do your assignment and next Saturday bring it in,

turn it in and they would criticize it. A written criticism would be attached to your drawings the next time you

returned. And if it was a good drawing, what they considered good quality, they gave you an honorable mention.

And at the end of the term if you had accumulated something like 10 honorable mentions, you were given a gold

pen which was inscribed. So that was a goal which all students worked toward, they were trying to get this little

gold pen. And so I won these little scholarships consistently until uh, from grade school to high school. But the

other, I guess, the other important thing that happened to me at least in terms of getting some kind of art

education as well as being associated with other young people who were interested in be coming artists, was

that when I was about 14 there was a club, an art club in the Negro neighborhood I lived in and was composed of

all Negro artists. They used to meet on Sundays at various members houses. And we would hold little

exhibitions and occasionally have life drawing classes and things.

BETTY L. HOAG: Was this under the direction of any adult, particularly?

CHARLES WHITE: Well, the ages varied. I was the youngest, I was 14. And there was some there, you know, in

their early forties, I mean people who were all interested in art. The organization was called the Arts-Crafts

Guild. The thing was interesting because they were all working people, young people. And it was also interesting

because nobody in this group had really had any normal art education. They were all amateurs except one

individual who was sort of the president of the group. His name was George E. Neal, and George had gone to the

Art Institute for a couple of years, and he was quite a talented young man. He must have been at that time in his

early twenties, and he would more or less guide us and gave us the real, formal knowledge that he was

acquiring in school. So this went on for a couple of years. Then we decided that we had to find some better way

to equip ourselves other than just through one person. We felt that there was enough talent in our organization

to warrant other people going to art school, or having an opportunity to go. So, what we did, we devised a way. We said, “We’ll use every means possible, even having little parties, every means possible to collect enough

money to send one of our members to the Art Institute of Chicago to take at least one class a week.

their early forties, I mean people who were all interested in art. The organization was called the Arts-Crafts

Guild. The thing was interesting because they were all working people, young people. And it was also interesting

because nobody in this group had really had any normal art education. They were all amateurs except one

individual who was sort of the president of the group. His name was George E. Neal, and George had gone to the

Art Institute for a couple of years, and he was quite a talented young man. He must have been at that time in his

early twenties, and he would more or less guide us and gave us the real, formal knowledge that he was

acquiring in school. So this went on for a couple of years. Then we decided that we had to find some better way

to equip ourselves other than just through one person. We felt that there was enough talent in our organization

to warrant other people going to art school, or having an opportunity to go. So, what we did, we devised a way. We said, “We’ll use every means possible, even having little parties, every means possible to collect enough

money to send one of our members to the Art Institute of Chicago to take at least one class a week.

BETTY L. HOAG: With the idea that he would bring back this information?

CHARLES WHITE: He would bring back information to us so that we could become further trained. So, what we

did, we had a little competition and one of the members would win and we would send him to the art school and

to whatever class we could afford. I mean, whatever classes he attended they found out how much we could

afford to give to this scholarship fund so we just went on for a number of years, and that’s how some of the

people got their education.

did, we had a little competition and one of the members would win and we would send him to the art school and

to whatever class we could afford. I mean, whatever classes he attended they found out how much we could

afford to give to this scholarship fund so we just went on for a number of years, and that’s how some of the

people got their education.

BETTY L. HOAG: Were you one of those chosen?

CHARLES WHITE: No, I never won the competition. The older people were much more often, because remember

that around this time I was 14 or 15. I didn’t enter until I was about 16 years old.

that around this time I was 14 or 15. I didn’t enter until I was about 16 years old.

BETTY L. HOAG: You were probably still in school then weren’t you?

CHARLES WHITE: Oh yes, I was still going to school and having a great many problems in school. I was always

painting, and I grew to hate school primarily because, as I said, I had become quite a, I guess an individualist in

a lot of my thinking. And because I had been pretty much of a lonely child. I found the kind of, any kind of

institution, formal institution like a school very difficult to adjust to and I had certain interests—I felt that the

high school I went to didn’t—

painting, and I grew to hate school primarily because, as I said, I had become quite a, I guess an individualist in

a lot of my thinking. And because I had been pretty much of a lonely child. I found the kind of, any kind of

institution, formal institution like a school very difficult to adjust to and I had certain interests—I felt that the

high school I went to didn’t—

BETTY L. HOAG: I’m sorry, I knew this tape was going to end.

[END OF TAPE 1 – SIDE 1]

[TAPE 1 – SIDE 2]

[END OF TAPE 1 – SIDE 1]

[TAPE 1 – SIDE 2]

BETTY L. HOAG: This is Betty Lochrie Hoag on March 9th interviewing the artist Charles White in Los Angeles. Mr. White, you mentioned being such a lonely child. Were you an only child or was it because of your art?

CHARLES WHITE: No, I was an only child and since loneliness came out of both my home set-up and besides

being extremely poor, my father was an alcoholic and that made for many domestic problems that reacted on

me. My sensitivities were repelled by his constant drinking and the embarrassment it caused me.

being extremely poor, my father was an alcoholic and that made for many domestic problems that reacted on

me. My sensitivities were repelled by his constant drinking and the embarrassment it caused me.

BETTY L. HOAG: Trouble for your mother too, would make it hard for a little boy.

CHARLES WHITE: Right, and I’d say this carried over into all my early social life, certainly in school. It was also

the problem, I think, of awareness of being a Negro, and what it meant in terms of, even in school. The high

school I went to which was predominantly white. I guess it was about 70 percent white at the time. As an

example, as I indicated, I was interested in acting. Up until my junior year I had been designing most of the sets

for the school plays and drawing all the posters and things and I began to get interested in and curious about

acting, and this was just unheard of in that school, none of the Negro students were ever allowed to act. They

could participate in the broader entertainment of the school, you know, the band performances or something like

this, but not in the school drama.

the problem, I think, of awareness of being a Negro, and what it meant in terms of, even in school. The high

school I went to which was predominantly white. I guess it was about 70 percent white at the time. As an

example, as I indicated, I was interested in acting. Up until my junior year I had been designing most of the sets

for the school plays and drawing all the posters and things and I began to get interested in and curious about

acting, and this was just unheard of in that school, none of the Negro students were ever allowed to act. They

could participate in the broader entertainment of the school, you know, the band performances or something like

this, but not in the school drama.

BETTY L. HOAG: That seems amazing today, doesn’t it.

CHARLES WHITE: It may be; I’m sure that in certain cities it’s probably not that restricting, but it was then.

BETTY L. HOAG: Well then you were deterred from going on with this as far as any of the school plays? They

wouldn’t even give you a chance for parts?

wouldn’t even give you a chance for parts?

CHARLES WHITE: No, they wouldn’t even consider it. And so this became a problem. Also, there were no negroes

were allowed to be members of the Hi-Y Club. With a lot of other problems at school and my own in ability to

make the adjustments to them I became so anti-school that I became a constant truant. Whenever I’d walk out

of the house and it would be a nice beautiful day and I’d get half way to school and say, “This is ridiculous!

What’s the use of going to school?” I much preferred spending time in the library or going to the Art Institute,

which I generally did. So, uh—

were allowed to be members of the Hi-Y Club. With a lot of other problems at school and my own in ability to

make the adjustments to them I became so anti-school that I became a constant truant. Whenever I’d walk out

of the house and it would be a nice beautiful day and I’d get half way to school and say, “This is ridiculous!

What’s the use of going to school?” I much preferred spending time in the library or going to the Art Institute,

which I generally did. So, uh—

BETTY L. HOAG: Did the school check up on this?

CHARLES WHITE: No problem. And another thing which is probably the thing that really set it off long before the

Hi-Y and the school drama was that, as I said, books had been my second greatest passion in life. And by the

time I got into high school I’d read all the books of Jack London. I had read Mark Twain, all of his works. I was

going to go through the alphabet in the library. I started with the A’s and it didn’t matter what the subject was,

fiction or non fiction, or what it was, I was just going to read right through. So I started and naturally I didn’t even

get halfway, but this was the course I took. Somehow in all this exploring of books and different kinds of books

on different subjects, I came across quite accidentally in the library one of the most definitive and one of the

most important books that had ever been done on the culture of the Negro, which was a book called The New

Negro by Dr. Alain Locke who was Professor of Philosophy, chairman of the Philosophy Department at Howard

University. Dr. Locke was the authority on American Negro culture, with a particular interest to me because of

his own special interest in art, the history of the Negro artist in America.

Hi-Y and the school drama was that, as I said, books had been my second greatest passion in life. And by the

time I got into high school I’d read all the books of Jack London. I had read Mark Twain, all of his works. I was

going to go through the alphabet in the library. I started with the A’s and it didn’t matter what the subject was,

fiction or non fiction, or what it was, I was just going to read right through. So I started and naturally I didn’t even

get halfway, but this was the course I took. Somehow in all this exploring of books and different kinds of books

on different subjects, I came across quite accidentally in the library one of the most definitive and one of the

most important books that had ever been done on the culture of the Negro, which was a book called The New

Negro by Dr. Alain Locke who was Professor of Philosophy, chairman of the Philosophy Department at Howard

University. Dr. Locke was the authority on American Negro culture, with a particular interest to me because of

his own special interest in art, the history of the Negro artist in America.

BETTY L. HOAG: What a bonanza for you!

CHARLES WHITE: This book opened my eyes, because I heard names, read names, read of people that I’d never

heard of before, like Countee Cullen, the great Negro poet. Heard Paul Robeson’s name for the first time. Most of

the great literary figures of the early twenties, when it was a period which they called “The Negro Rennaissance”

when the first blossoming of Negro culture in America really came to a head. And this book dealt specifically with

that. Well, once I found this one book, then I began to search for other books on Negroes, which led to Negro

historical figures, individuals that played a role in the abolition of slavery, names like Denmark Vesey, who led a

slave revolt. Nat Turner who also led a slave revolt. Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington,

Frederick Douglass, all were names that in later years I’ve become quite well read on. For the first time, at 14

years old, these names came to my mind. I became aware the Negroes had a history in America. So, when I

went to high school and had to take U.S. History, the first year I got through fine. Then the second year I decided

that—I began to question why these names weren’t mentioned in the standard U.S. History which we all studied,

which was Beard’s History [of the United States]. The only Negro name that was mentioned in there was Crispus

Attucks, the first man to die in the American Revolution and there was one sentence on Crispus Attucks. There

was nothing else throughout the whole of Beard’s History. So I read this and I remember the first day of class I

had in my second year, I raised this question to the teacher and she told me to sit down. She didn’t even bother

to be polite about it.

heard of before, like Countee Cullen, the great Negro poet. Heard Paul Robeson’s name for the first time. Most of

the great literary figures of the early twenties, when it was a period which they called “The Negro Rennaissance”

when the first blossoming of Negro culture in America really came to a head. And this book dealt specifically with

that. Well, once I found this one book, then I began to search for other books on Negroes, which led to Negro

historical figures, individuals that played a role in the abolition of slavery, names like Denmark Vesey, who led a

slave revolt. Nat Turner who also led a slave revolt. Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington,

Frederick Douglass, all were names that in later years I’ve become quite well read on. For the first time, at 14

years old, these names came to my mind. I became aware the Negroes had a history in America. So, when I

went to high school and had to take U.S. History, the first year I got through fine. Then the second year I decided

that—I began to question why these names weren’t mentioned in the standard U.S. History which we all studied,

which was Beard’s History [of the United States]. The only Negro name that was mentioned in there was Crispus

Attucks, the first man to die in the American Revolution and there was one sentence on Crispus Attucks. There

was nothing else throughout the whole of Beard’s History. So I read this and I remember the first day of class I

had in my second year, I raised this question to the teacher and she told me to sit down. She didn’t even bother

to be polite about it.

ESG: Reread this section! Speaks to what’s currently happening in our society.

BETTY L. HOAG: She was undoubtedly ashamed because she knew nothing about it herself!

CHARLES WHITE: So I sat down and I sat out that whole class. I made up my mind I was going to sit out this

whole class the rest of the term. I was not going to participate in it until somebody gave me a satisfactory

explanation of why it was so and if not why weren’t they included. They wouldn’t let me drop U.S. History, so I

didn’t participate. When the term paper came, I signed my name and turned it in blank. When she asked for oral

recitation I would not raise my hand, she’d call on me and I would say, “I don’t know,” and sit down. This was my

only way of fighting.

whole class the rest of the term. I was not going to participate in it until somebody gave me a satisfactory

explanation of why it was so and if not why weren’t they included. They wouldn’t let me drop U.S. History, so I

didn’t participate. When the term paper came, I signed my name and turned it in blank. When she asked for oral

recitation I would not raise my hand, she’d call on me and I would say, “I don’t know,” and sit down. This was my

only way of fighting.

BETTY L. HOAG: Your own sit-down strike!

CHARLES WHITE: I wasn’t equipped to fight it any other way. This was the only tool I knew to use to fight it. And

so naturally, the dean called me in and they tried to threaten me with expulsion.

so naturally, the dean called me in and they tried to threaten me with expulsion.

BETTY L. HOAG: Didn’t you explain this thing to him?

CHARLES WHITE: I wasn’t articulate enough to explain in the full sense. I became a joke in the class. The

teacher…what I was doing—even in her other class, she made them aware of what I was doing so I sort of

became a little joke around the school. So all these things led to…as I say, again, not being able to participate in

certain social clubs in school, and the Drama Club, it led to the truancy I referred to. So I flunked for a whole

year. The only classes I passed in were art classes and English Literature. In my second year, they introduced

Sociology and Philosophy class, and I passed in those. But what it wound up meaning in the end was that it took

me five years to get out of high school. So I was 19 when I finished high school.

teacher…what I was doing—even in her other class, she made them aware of what I was doing so I sort of

became a little joke around the school. So all these things led to…as I say, again, not being able to participate in

certain social clubs in school, and the Drama Club, it led to the truancy I referred to. So I flunked for a whole

year. The only classes I passed in were art classes and English Literature. In my second year, they introduced

Sociology and Philosophy class, and I passed in those. But what it wound up meaning in the end was that it took

me five years to get out of high school. So I was 19 when I finished high school.

BETTY L. HOAG: Well, this art group that was formed must have been a god-send to you.

CHARLES WHITE: It was. It was the first time I met other artists. I met white artists I had never known before,

and people whose names were important locally. And I used to go around and clean up the studios for Edward

Millman for instance, who was a very important muralist at that time, did one of the most important murals.

and people whose names were important locally. And I used to go around and clean up the studios for Edward

Millman for instance, who was a very important muralist at that time, did one of the most important murals.

BETTY L. HOAG: Your concept of history and realizing that the culture of the Negro should be in it is so

interesting. You were born just way too soon, before your time! I noticed just last month our California Historical

Journal they came out with an article about “The Negro as a Cowboy,” which is simply fascinating.

interesting. You were born just way too soon, before your time! I noticed just last month our California Historical

Journal they came out with an article about “The Negro as a Cowboy,” which is simply fascinating.

CHARLES WHITE: I want to get that book, it sounds like a fascinating book.

BETTY L. HOAG: I’d like to too, I read the review of it. But we certainly are aware of it today in all different

phases. It’s interesting, in fact it’s unbelievable, that a school board, even though you weren’t very articulate,

couldn’t understand this and do something to develop you.

phases. It’s interesting, in fact it’s unbelievable, that a school board, even though you weren’t very articulate,

couldn’t understand this and do something to develop you.

CHARLES WHITE: Yeah, well, see most of the teachers in most of my other classes weren’t as sensitive about

these things. Now my art teachers were, they were very sensitive about every facet of me, and I think if it hadn’t

been for them I wouldn’t have survived. The only reason I finished, finally got down to business and really

finished high school was because of their sensitivity, and because my mother became so upset by my attitude

and what I was doing, terribly upset. Everybody treated me as a delinquent which I wasn’t by any means.

these things. Now my art teachers were, they were very sensitive about every facet of me, and I think if it hadn’t

been for them I wouldn’t have survived. The only reason I finished, finally got down to business and really

finished high school was because of their sensitivity, and because my mother became so upset by my attitude

and what I was doing, terribly upset. Everybody treated me as a delinquent which I wasn’t by any means.

BETTY L. HOAG: But you felt you had to show them you could get through.

CHARLES WHITE: This terrible handicap that sometimes a teenager will have when he isn’t equipped verbally or

any other way to fight and express the things he feels inside.

any other way to fight and express the things he feels inside.

BETTY L. HOAG: Teenagers have this anyway. I mean, they all have it whether they’re figments of their

imagination or what, it’s part of being a teenager.

imagination or what, it’s part of being a teenager.

CHARLES WHITE: But I finally got out and another thing, when I was about, oh, in my last year I won three

scholarships. Now the first two scholarships were to two local art schools in Chicago, mostly geared to

commercial art, but I was denied admittance to the school when they found out I was a Negro. So this had a

cruel, traumatic effect on me to say the least. But fortunately, in the last national competition in high school was —the Art Institute of Chicago offers scholarships and holds competitions annually, and I won the competition

that year, which was 1937, and so I finally got an opportunity to take some formal training. This was a great

moment. You have no idea what a thrill that was.

scholarships. Now the first two scholarships were to two local art schools in Chicago, mostly geared to

commercial art, but I was denied admittance to the school when they found out I was a Negro. So this had a

cruel, traumatic effect on me to say the least. But fortunately, in the last national competition in high school was —the Art Institute of Chicago offers scholarships and holds competitions annually, and I won the competition

that year, which was 1937, and so I finally got an opportunity to take some formal training. This was a great

moment. You have no idea what a thrill that was.

BETTY L. HOAG: Now was this a full scholarship?

CHARLES WHITE: Yes, it was a full scholarship to be a full-time student.

BETTY L. HOAG: Now wasn’t that great! Now were there any teachers who particularly influenced you there? Any

time there are that you’d like to get on the tape do tell us about them.

time there are that you’d like to get on the tape do tell us about them.

CHARLES WHITE: There was not really any particular teacher. There were some I related to more and that

inspired me, but not to any significant degree. I think I was mostly inspired by other artists in Chicago who were

doing things that I saw—older artists like Mitchell Siporin. He is quite a nationally known artist, and he had a

great influence on my whole thinking. Then there was Francis Chapin, who was another painter, and Aaron

Bohrod was another painter at the time who had a tremendous influence on my painting.

inspired me, but not to any significant degree. I think I was mostly inspired by other artists in Chicago who were

doing things that I saw—older artists like Mitchell Siporin. He is quite a nationally known artist, and he had a

great influence on my whole thinking. Then there was Francis Chapin, who was another painter, and Aaron

Bohrod was another painter at the time who had a tremendous influence on my painting.

BETTY L. HOAG: Were they all teaching at the Institute?

CHARLES WHITE: No, they weren’t teaching there, that’s what I say, the teachers themselves—My greatest

inspiration came from people outside the Art Institute. The difficulty I had in art school, even though I had a

scholarship, was that financially it was difficult to maintain myself. For instance, I used to have to walk, we lived

5300 South and the Art Institute was at Adams and Michigan and that’s about 60 blocks almost, and I very often

had to walk because I had no car fare. I didn’t have any money to buy materials so one of the instructors let me

use his account at art supplies store, so I used to get material that way. So it was a question of hustling all the

time for material. Finally it got so we reached a point, we got so desperate I had to hunt a job. So this is when I

got a job as a valet and cook to one of the local artists in Chicago whose name I—.Antonio Beneduce. He made a

great deal of money doing work for interior decorating firms. He advertised at the school for a valet and a cook. Well, I had never cooked in my entire life, I didn’t know one thing about cooking. So, a cute little story of the way

I learned is that the first time I had to cook a meal for him fortunately he wasn’t home, so I called up my mother

and she told me how to cook a full five course dinner over the phone. The phone must’ve been off the hook

about three and a half to four hours and I cooked this whole dinner over the phone. Every time she’d tell me

something I’d run back and do it and come back to the phone. [Laughs] Let’s see, I held that job for about a

year.

inspiration came from people outside the Art Institute. The difficulty I had in art school, even though I had a

scholarship, was that financially it was difficult to maintain myself. For instance, I used to have to walk, we lived

5300 South and the Art Institute was at Adams and Michigan and that’s about 60 blocks almost, and I very often

had to walk because I had no car fare. I didn’t have any money to buy materials so one of the instructors let me

use his account at art supplies store, so I used to get material that way. So it was a question of hustling all the

time for material. Finally it got so we reached a point, we got so desperate I had to hunt a job. So this is when I

got a job as a valet and cook to one of the local artists in Chicago whose name I—.Antonio Beneduce. He made a

great deal of money doing work for interior decorating firms. He advertised at the school for a valet and a cook. Well, I had never cooked in my entire life, I didn’t know one thing about cooking. So, a cute little story of the way

I learned is that the first time I had to cook a meal for him fortunately he wasn’t home, so I called up my mother

and she told me how to cook a full five course dinner over the phone. The phone must’ve been off the hook

about three and a half to four hours and I cooked this whole dinner over the phone. Every time she’d tell me

something I’d run back and do it and come back to the phone. [Laughs] Let’s see, I held that job for about a

year.

ESG: Penniless, he was forced to walk daily to the Art Institute–from Bronzeville! And he continued to persevere! He became an OLD MASTER. —I will never complain again.

BETTY L. HOAG: You didn’t cook the same meal over and over did you?

CHARLES WHITE: No, every evening when I’d go home from work, my mother, she’d brief me, and then she’d

write out things. So he never knew, and I became a pretty good cook. He never learned but the only thing he

found out, he used to worry about his phone bill, it was so enormous. Naturally, it went up every day! That first

year in art school I also got another job with a Catholic high school, St. Elizabeth’s Catholic High School, which I

taught one class to the senior students.

write out things. So he never knew, and I became a pretty good cook. He never learned but the only thing he

found out, he used to worry about his phone bill, it was so enormous. Naturally, it went up every day! That first

year in art school I also got another job with a Catholic high school, St. Elizabeth’s Catholic High School, which I

taught one class to the senior students.

BETTY L. HOAG: In painting?

CHARLES WHITE: Yes, well, drawing and painting. It was a general high school kind of teaching. And so I held

those two jobs and yet I finished two years of work in one at the Art Institute.

those two jobs and yet I finished two years of work in one at the Art Institute.

BETTY L. HOAG: Good heavens! And you also had another scholarship that year be cause you had a National

School Award, didn’t you?

School Award, didn’t you?

CHARLES WHITE: That was the same year I graduated from high school, 1937, I did the Scholastic Magazine

Award, a national award. I won a couple of prizes in that year.

Award, a national award. I won a couple of prizes in that year.

BETTY L. HOAG: Goodness, that must have been about the time of the Federal Art Project. Let’s jump that and

come back to it if you don’t mind so we can develop it a little more. I think the next place I take you then was

the Art Students League in New York. Is that right?

come back to it if you don’t mind so we can develop it a little more. I think the next place I take you then was

the Art Students League in New York. Is that right?

CHARLES WHITE: No, the next place I went to was New Orleans which was around 1941. I got a job teaching

there at Dillard University, in New Orleans. I stayed there for about a year and by this time I was also married to

a young woman from Washington who was quite an artist. She is a tremendous artist, a sculptor, primarily.

there at Dillard University, in New Orleans. I stayed there for about a year and by this time I was also married to

a young woman from Washington who was quite an artist. She is a tremendous artist, a sculptor, primarily.

BETTY L. HOAG: What was her name?

CHARLES WHITE: Elizabeth Catlett. I think she is now the head of the Sculpture Department at the University of

Mexico. But she was teaching at Dillard too.

Mexico. But she was teaching at Dillard too.

BETTY L. HOAG: Did you meet her there?

CHARLES WHITE: We met in Chicago. She’d gotten her master’s at Iowa where she had studied under Grant

Wood, and she came to Chicago and studied at the Art Institute for one summer. We met and got married and

went to New Orleans, and I was hired there too, so we worked there for about a year. And then I got a Julius

Rosenwald Fellowhip which is the reason we left Dillard. The Julius Rosenwald Fellowship. And we went to New

York. That’s where I entered the Art Students League and took a course in graphics with Harry Sternberg.

Wood, and she came to Chicago and studied at the Art Institute for one summer. We met and got married and

went to New Orleans, and I was hired there too, so we worked there for about a year. And then I got a Julius

Rosenwald Fellowhip which is the reason we left Dillard. The Julius Rosenwald Fellowship. And we went to New

York. That’s where I entered the Art Students League and took a course in graphics with Harry Sternberg.

BETTY L. HOAG: (Speaking to someone else present) Now Mr. Horowitz, didn’t Mr. Sternberg exhibit here at your

gallery just recently? He’s the gentleman I was trying to remember, he had also been on the Project. One day I’ll

have to interview you about him and get him out here too.

gallery just recently? He’s the gentleman I was trying to remember, he had also been on the Project. One day I’ll

have to interview you about him and get him out here too.

CHARLES WHITE: He was a great teacher.

HOROWITZ: He comes out here once in a while, he teaches out at Idlewild.

BETTY L. HOAG: Maybe next summer I can catch him when he comes back.

HOROWITZ: If he does come I’ll be glad to get him down here.

BETTY L. HOAG: I had a friend from Palm Springs who was so disappointed to have missed the show. She said

she’d known him up there and I thought she must have meant someone else.

she’d known him up there and I thought she must have meant someone else.

HOROWITZ: No, same one.

BETTY L. HOAG: Thank you.

HOROWITZ: I have a folder on him here I’d be glad to give you, if you could use it.

HOROWITZ: I have a folder on him here I’d be glad to give you, if you could use it.

BETTY L. HOAG: Boy! I’d love to see it!

[Addressing Charles White]

Mr. White, we were talking about this Rosenwald Fellowship at the Art Students League. That was in 1942 to

1943 that you were there.

[Addressing Charles White]

Mr. White, we were talking about this Rosenwald Fellowship at the Art Students League. That was in 1942 to

1943 that you were there.

CHARLES WHITE: Yes. Part of the project under the fellowship was to do three months of studying at the Art

Students League and the rest of the time was to be devoted to doing a mural at some Negro college in the

South. And the mural was to depict the Negro’s contribution to democracy in America, and the school for the

mural to be presented or to be executed, was to be my choice, for which I took a trip to a number of Negro

universities and finally picked Hampton Institute in Hampton Virginia where I spent the final nine months of my

fellowship executing the mural at the school.

Students League and the rest of the time was to be devoted to doing a mural at some Negro college in the

South. And the mural was to depict the Negro’s contribution to democracy in America, and the school for the

mural to be presented or to be executed, was to be my choice, for which I took a trip to a number of Negro

universities and finally picked Hampton Institute in Hampton Virginia where I spent the final nine months of my

fellowship executing the mural at the school.

BETTY L. HOAG: Was it in the library?

CHARLES WHITE: It was in one of the main auditoriums, they had two auditoriums there and it was in one of

them.

them.

BETTY L. HOAG: And just very briefly, what was it?

CHARLES WHITE: What was the mural?

BETTY L. HOAG: What was the subject, and how did you carry it out?

CHARLES WHITE: Well, it depicted, I started with the American Revolution, depicting Crispus Attucks as the first

man to die in the Revolution, came on through using individuals like Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington,

George Carver, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, and Marian Anderson. The object was to take the

contributions both through physical revolt of fighting for the abolition of slavery, and also the contributions that

had been made in the sciences as well as the arts, as well as politics. So to cover the contribution to many facets

of American life, just what was the key to this whole struggle.

man to die in the Revolution, came on through using individuals like Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington,

George Carver, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, and Marian Anderson. The object was to take the

contributions both through physical revolt of fighting for the abolition of slavery, and also the contributions that

had been made in the sciences as well as the arts, as well as politics. So to cover the contribution to many facets

of American life, just what was the key to this whole struggle.

BETTY L. HOAG: With interwoven scenes it must have been a magnificent mural!

CHARLES WHITE: It was a big job, I think the mural was something like 18 by 60 feet so it was an enormous job

which I executed with egg tempera directly on the wall which was a very interesting experience at Hampton

because the head of the Art Department there was the man who became internationally known both as a

teacher, an educator. His name was Dr. Viktor Lowenfeld. He was an Austrian.

which I executed with egg tempera directly on the wall which was a very interesting experience at Hampton

because the head of the Art Department there was the man who became internationally known both as a

teacher, an educator. His name was Dr. Viktor Lowenfeld. He was an Austrian.

BETTY L. HOAG: You don’t know the spelling?

CHARLES WHITE: I think it’s L-O-W-E-N-F-I-E-L-D, I’m not sure, but he is Viktor spelled with a K.

BETTY L. HOAG: Just as a matter of interest because I think you did a mural on the Project before this, is that

where you learned egg tempera?

where you learned egg tempera?

CHARLES WHITE: Yes, I first learned on the Project. I first learned by being an assistant to a mural painter on one

mural. Then I was given a commission to do one for a branch of the Chicago Public Library.

mural. Then I was given a commission to do one for a branch of the Chicago Public Library.

BETTY L. HOAG: We’ll come back to that. I’d like to get it in the record when we can see influence from the

Project in a man’s later work. Always sort of fun to know things that helped. Let’s see, after that, I have you in

Mexico. You probably jumped around more than that and I just don’t have reference to it.

Project in a man’s later work. Always sort of fun to know things that helped. Let’s see, after that, I have you in

Mexico. You probably jumped around more than that and I just don’t have reference to it.

CHARLES WHITE: After, the fellowships, I had two consecutive Rosenwald Fellowships, then I was drafted into the

Army in 1944. I spent about a year in a camouflage unit of the Engineers.

Army in 1944. I spent about a year in a camouflage unit of the Engineers.

BETTY L. HOAG: Where were you stationed?

CHARLES WHITE: I was stationed at Camp Ellis, Illinois. I did my basic training then. Then I went to Jefferson

Barracks in Missouri. As a result of fighting the floods in Missouri—the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers flooded that

year—I developed pleurisy. I was sent to a base hospital. In draining the fluid of pleurisy off my chest they found

a tubercular condition, which, I was given a medical discharge from the Army, and was sent to a hospital. There I

spent two years the first time and later was to spend two more years as a result of that.

Barracks in Missouri. As a result of fighting the floods in Missouri—the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers flooded that

year—I developed pleurisy. I was sent to a base hospital. In draining the fluid of pleurisy off my chest they found

a tubercular condition, which, I was given a medical discharge from the Army, and was sent to a hospital. There I

spent two years the first time and later was to spend two more years as a result of that.

BETTY L. HOAG: Your speaking of being a camouflage artist and fighting floods instead made me think of Ted

Gilien. I interviewed him earlier this week and he was a camouflage artist sent to New Guinea and what he did

was to move ammunition dumps.

Gilien. I interviewed him earlier this week and he was a camouflage artist sent to New Guinea and what he did

was to move ammunition dumps.

CHARLES WHITE: Well, I painted signs for quite a while as a camoufleur. Mostly on cans that said “Edible” and

“Nonedible”. And I also had the opportunity of painting the Mess Hall once.

“Nonedible”. And I also had the opportunity of painting the Mess Hall once.

BETTY L. HOAG: Outside or inside? Do you mean a mural?

CHARLES WHITE: No, just painting with flat paint. Then finally they gave me a mural to do for one of the Noncom clubs at the post. I wound up with a rating of Corporal.

BETTY L. HOAG: Do you think that mural is still there at the base?

CHARLES WHITE: I’m sure it isn’t.

BETTY L. HOAG: Well, let’s see. That was ‘44 to ‘46 then?

CHARLES WHITE: Yes, between the hospital and the Army. After I was discharged from the hospital I went to

Mexico.

Mexico.

BETTY L. HOAG: Now was this on another grant of some kind?

CHARLES WHITE: No. Just purely on our own. We went down there, I think. My wife had a fellowship—that’s what

it was, she had a fellowship, so we went down and spent a couple of years there.

it was, she had a fellowship, so we went down and spent a couple of years there.

BETTY L. HOAG: You did free-lance painting?

CHARLES WHITE: Yeah, I was painting. By this time I had become a member of the ACA Gallery, I had a one-man

show in New York and—

show in New York and—

BETTY L. HOAG: I’m sorry, I don’t know what an ACA is.

CHARLES WHITE: Well, it’s called the ACA Gallery, I think it stands for “American Contemporary Art.” It’s known

by its initials rather than its full name. So, my paintings had begun to sell very well, and because my wife had a

fellowship we were able to live relatively well. And I went to school at the Mexican Government School of Mexico

called Escuela de Pientura y Scultura, which it means “School of Painting and Sculpture.” And it’s known as “The

Esmaralda”, because that is the name of the street it is on; that’s not really the name of the school, but

everybody calls it by that name.

by its initials rather than its full name. So, my paintings had begun to sell very well, and because my wife had a

fellowship we were able to live relatively well. And I went to school at the Mexican Government School of Mexico

called Escuela de Pientura y Scultura, which it means “School of Painting and Sculpture.” And it’s known as “The

Esmaralda”, because that is the name of the street it is on; that’s not really the name of the school, but

everybody calls it by that name.

BETTY L. HOAG: Is that the same as the Talier de Graphica?

CHARLES WHITE: No, that was the Graphics Workshop where all the artists who worked in medias of lithography

and woodcuts were either members or did their work. There was quite a famous group there, and I both studied

there and became a member of the Tallera.

and woodcuts were either members or did their work. There was quite a famous group there, and I both studied

there and became a member of the Tallera.

BETTY L. HOAG: Now is that where you knew Leopolda Mendez? And Siqueiros?

CHARLES WHITE: Yeah, I lived with Siqueiros for about a year in the same house. He owned a big house and he

let us have a place. And Pablo O’Higgins worked at the Talier and Orozco did some prints there as well as Diego

Rivera.

let us have a place. And Pablo O’Higgins worked at the Talier and Orozco did some prints there as well as Diego

Rivera.

BETTY L. HOAG: Do you think the Mexican work influenced your own?

CHARLES WHITE: It had a tremendous influence on me. I guess the two things that in my earlier life that had the

most influence was both studying with Harry Sternberg, who was a great teacher and opened my eyes for the

first time opened my eyes to my feelings that I had never been able to quite pin down to the kind of work that I

was doing. He brought it out, so to speak. And Harry was the most important teacher I ever had, as well as the

experience of Mexico itself, because of the nature of the kind of stuff I was doing, was more geared to “social

realism” in quotes. I found that I found people in Mexico who were also dealing with the same kind of approach

(in terms of content) that was just my mental experience.

most influence was both studying with Harry Sternberg, who was a great teacher and opened my eyes for the

first time opened my eyes to my feelings that I had never been able to quite pin down to the kind of work that I

was doing. He brought it out, so to speak. And Harry was the most important teacher I ever had, as well as the

experience of Mexico itself, because of the nature of the kind of stuff I was doing, was more geared to “social

realism” in quotes. I found that I found people in Mexico who were also dealing with the same kind of approach

(in terms of content) that was just my mental experience.

BETTY L. HOAG: I know that you have done so much work in graphics and someplace it said that you do an

average of about 4 oil paintings a year. Was Sternberg a painter in all these mediums, and in Mexico were you

doing all different mediums?

average of about 4 oil paintings a year. Was Sternberg a painter in all these mediums, and in Mexico were you

doing all different mediums?

CHARLES WHITE: Well, Sternberg, while being a painter, was also better known as a graphic artist. I studied

primarily graphics with him, and I guess in my work I’ve always had a stronger leaning for graphics and I found

my own talents were best suited for the black and white media rather than color, and I have never felt that color

in itself was absolutely necessary for an artist to be an artist. In other words, you can say if Kollwitz, Käthe

Kollwitz, if she did a painting, nobody has ever seen it, that I know of, yet she was a great artist. If Daumier or

Goya had never painted, they still would have been great artists. So, I always felt this way about black and

white. And I used to feel a little apologetic for not painting more, but I’ve done, actually hundreds of paintings in

my life. For instance, on the WPA I had to do a painting every 5 weeks, and I was on it for 3 years, so that leaves

a lot of paintings.

primarily graphics with him, and I guess in my work I’ve always had a stronger leaning for graphics and I found

my own talents were best suited for the black and white media rather than color, and I have never felt that color

in itself was absolutely necessary for an artist to be an artist. In other words, you can say if Kollwitz, Käthe

Kollwitz, if she did a painting, nobody has ever seen it, that I know of, yet she was a great artist. If Daumier or

Goya had never painted, they still would have been great artists. So, I always felt this way about black and

white. And I used to feel a little apologetic for not painting more, but I’ve done, actually hundreds of paintings in

my life. For instance, on the WPA I had to do a painting every 5 weeks, and I was on it for 3 years, so that leaves

a lot of paintings.

BETTY L. HOAG: I think it’s so unusual today for a person to be doing graphics like yours. When they’re such

great draftsmen, there are so few of them around and you’re such a marvelously accomplished draftsman. The

things just breathe right through and you don’t even think about there not being any color. I think if a person

can put that over—

great draftsmen, there are so few of them around and you’re such a marvelously accomplished draftsman. The

things just breathe right through and you don’t even think about there not being any color. I think if a person

can put that over—

CHARLES WHITE: I guess the most important thing is to, for me has always been to say something that is

meaningful, and much more important than the media I use. And whatever media that I could do it strongest,

that’s the media I’ve always used. That’s why murals are extremely important to me, even though it’s hard to

get mural commissions these days, but murals I’ve always felt very strong to because it’s allowed me the room

to say the kind of things—

meaningful, and much more important than the media I use. And whatever media that I could do it strongest,

that’s the media I’ve always used. That’s why murals are extremely important to me, even though it’s hard to

get mural commissions these days, but murals I’ve always felt very strong to because it’s allowed me the room

to say the kind of things—

BETTY L. HOAG: Well, in a certain sense you’re a documentary artist documenting not only historical things but

the ideas.

the ideas.

CHARLES WHITE: Yeah, the main point is that what really I’ve always tried to do, essentially I’ve boiled it down, mostly when people ask me a question, I’ve boiled it down to three things I’ve essentially tried to do, which I

think most artists have to do, is that I try to deal with truth as truth maybe in my personal interpretation of truth

and truth is a very spiritual sense—not “spiritual” meaning religiously spiritual, but “spiritual” in the sense of the

inner-man, so to speak. I try to deal with beauty, and beauty again as I see it in my personal interpretation of it,

the beauty in man, the beauty in life, the beauty, the most precious possession that man has is life itself. And

that essentially I feel that man is basically good. I have to start from this premise in all my work because I’m

almost psychologically and emotionally incapable of doing any meaningful work which has to do with something

I hate. I’ve tried it. There’s been a number of tragedies in my life, in my family’s life. My people on my mother’s

side come from Mississippi and we’ve had 5 lynchings in my family, 2 uncles and 3 cousins over a long span of

years. I’ve lived in the South, have had unpleasant personal experiences, been beaten up a couple of times,

once in New Orleans and once in Virginia. My people all lived in rural sections mostly, were all farmers, so, and

yet, at the same time I still maintain in spite of, again, my experiences, my family’s experience, tragedies, I still

feel that man is basically good.

think most artists have to do, is that I try to deal with truth as truth maybe in my personal interpretation of truth

and truth is a very spiritual sense—not “spiritual” meaning religiously spiritual, but “spiritual” in the sense of the

inner-man, so to speak. I try to deal with beauty, and beauty again as I see it in my personal interpretation of it,

the beauty in man, the beauty in life, the beauty, the most precious possession that man has is life itself. And

that essentially I feel that man is basically good. I have to start from this premise in all my work because I’m

almost psychologically and emotionally incapable of doing any meaningful work which has to do with something

I hate. I’ve tried it. There’s been a number of tragedies in my life, in my family’s life. My people on my mother’s

side come from Mississippi and we’ve had 5 lynchings in my family, 2 uncles and 3 cousins over a long span of

years. I’ve lived in the South, have had unpleasant personal experiences, been beaten up a couple of times,

once in New Orleans and once in Virginia. My people all lived in rural sections mostly, were all farmers, so, and

yet, at the same time I still maintain in spite of, again, my experiences, my family’s experience, tragedies, I still

feel that man is basically good.

ESG: Heartbreaking…

BETTY L. HOAG: Well, it certainly shows in your work.

CHARLES WHITE: The other thing I try to deal with, the third point, is dignity. And I think that once man is robbed

of his dignity he is nothing. And I try to take the sense, when I deal with Negro people primarily in terms of

image I try to give it the meaning of universality to it. I don’t address myself primarily to the Negro people. They

certainly are key, you know, and a major part of the audience that I address myself to, but generally I use an

image in a more formal, universal sense than is sometimes understood by critics or people who see it.

of his dignity he is nothing. And I try to take the sense, when I deal with Negro people primarily in terms of

image I try to give it the meaning of universality to it. I don’t address myself primarily to the Negro people. They

certainly are key, you know, and a major part of the audience that I address myself to, but generally I use an

image in a more formal, universal sense than is sometimes understood by critics or people who see it.

BETTY L. HOAG: Like this wonderful print that Mr. Horowitz showed me of the Civil War woman with the rock

background. You have no sense of race; it isn’t there, it’s the idea of the strength of this woman combating right

as she sees it, that comes out of the picture. Is that what you mean?

background. You have no sense of race; it isn’t there, it’s the idea of the strength of this woman combating right

as she sees it, that comes out of the picture. Is that what you mean?

CHARLES WHITE: Exactly, what I want is so that when I say dignity and I say truth and I say beauty, these are

universal kinds of things that all men aspire to, within all men. So that I’m addressing myself for people I relate

to. Sometimes it may be difficult for white people to quite see it in these universal terms. I mean, I can

understand, say, if somebody saw it purely and they do, I get the sense that they sometimes don’t always see it

because somebody’s always asking me, “Why don’t you paint whites? You don’t paint anything other than

Negroes,” which indicates a certain lack of understanding and perceptiveness about this. But the point is that

I’ve had, as a Negro in America, I’ve related to images that had broader symbolic meanings, in spite of the fact

that the image might be white. For instance you know the Statue of Liberty is a nationally-known symbol of

something, well that Statue of Liberty symbolizing exactly—

universal kinds of things that all men aspire to, within all men. So that I’m addressing myself for people I relate

to. Sometimes it may be difficult for white people to quite see it in these universal terms. I mean, I can

understand, say, if somebody saw it purely and they do, I get the sense that they sometimes don’t always see it

because somebody’s always asking me, “Why don’t you paint whites? You don’t paint anything other than

Negroes,” which indicates a certain lack of understanding and perceptiveness about this. But the point is that

I’ve had, as a Negro in America, I’ve related to images that had broader symbolic meanings, in spite of the fact

that the image might be white. For instance you know the Statue of Liberty is a nationally-known symbol of

something, well that Statue of Liberty symbolizing exactly—

BETTY L. HOAG: You don’t ask if it is Irish—

CHARLES WHITE: It has Caucasian features but I can accept this image as symbolic of what the intent was

without seeing it and saying, “well, why can’t it be a black face up there?”, you know. You know the thousands of

images we have, Santa Claus, well, since I always feel that the artist only does meaningful things when he

draws upon that which is closest to him, and he uses that as a springboard to deal with a more broad, all-encompassing subject.

without seeing it and saying, “well, why can’t it be a black face up there?”, you know. You know the thousands of

images we have, Santa Claus, well, since I always feel that the artist only does meaningful things when he

draws upon that which is closest to him, and he uses that as a springboard to deal with a more broad, all-encompassing subject.

BETTY L. HOAG: Well, I think the amazing and wonderful thing is that I never see satire in your things. And of

course that would be a direct result of the way you feel about it. Satire has its place—I don’t mean it doesn’t—

but there’s no maliciousness, no cruelty in your work—

course that would be a direct result of the way you feel about it. Satire has its place—I don’t mean it doesn’t—

but there’s no maliciousness, no cruelty in your work—

CHARLES WHITE: I tried to do. Once I did some cartoons for a small paper in New York. And it was another

failure. I can’t do satirical things. I tried to do cartooning early in my life, couldn’t do a cartoon. I think I have a

sense of humor but I can’t use this media to do these kinds of things. I have to paint the things I love and

respect. While I pour out a great deal, there’s a certain amount of sadness in some of my things, a tragic kind of

expression maybe in their bodies and faces, but essentially I’m just dealing with trying to make man aware of all

these qualities.

failure. I can’t do satirical things. I tried to do cartooning early in my life, couldn’t do a cartoon. I think I have a

sense of humor but I can’t use this media to do these kinds of things. I have to paint the things I love and

respect. While I pour out a great deal, there’s a certain amount of sadness in some of my things, a tragic kind of

expression maybe in their bodies and faces, but essentially I’m just dealing with trying to make man aware of all

these qualities.

BETTY L. HOAG: I am eager sometimes to see some of the pictures you did of Belafonte. At one time I don’t know

if it ever came out, you were doing either a book or jacket, book-jacket, I don’t know which it was.

if it ever came out, you were doing either a book or jacket, book-jacket, I don’t know which it was.

CHARLES WHITE: I illustrated a book, Songs Belafonte Sings yes. It’s out.

BETTY L. HOAG: I’d love to see it.

CHARLES WHITE: Harry Belafonte and I have been very close friends for a number of years, long before he

became the very important figure in the arts that he is.

became the very important figure in the arts that he is.

BETTY L. HOAG: Everyone says he’s a great person.

CHARLES WHITE: He is, a magnificent person. Our friendship has been tremendously important to me. And he’s

been a great help to me in interpreting my work, this sensitivity and compassion for my work.

been a great help to me in interpreting my work, this sensitivity and compassion for my work.

BETTY L. HOAG: You also did titles for Anna Lucasta for the movies at one time. In fact, how did you get to

California?

California?

CHARLES WHITE: Well, I’ll tell you, after so many years, I spent 17 years in New York and my wife was born in

New York. (Incidentally, just for the record, I guess we ought to say that my first wife and I were divorced in

Mexico). Then Fran and I were married 15 years ago.

New York. (Incidentally, just for the record, I guess we ought to say that my first wife and I were divorced in

Mexico). Then Fran and I were married 15 years ago.

BETTY L. HOAG: So you must have come to Los Angeles about the ‘50s?

CHARLES WHITE: No, we came out in ‘57, I think, 1957. We had had it in New York. I had my health breakdown;

not real seriously, and then by that time we had both gotten fed up by the rat-race of New York and we wanted

something, felt that life must offer something more than big apartment buildings where you couldn’t see any